EID’s and genetic testing helps Hawkes Bay farmer tackle Campylobacter abortions in his mixed-aged ewes.

A Central Hawkes Bay farmer who has continually battled with Campylobacter losses in his high performing sheep flock has kindly shared his recent experience in the hope that it can provide other farmers with helpful information and practical suggestions if faced with a similar situation.

Running over 3,000 ewes in the Central Hawkes Bay ranges, the farm routinely vaccinates their hoggets

with 2 shots of Campyvax4® and 1 shot of Toxovax® premating, to protect the flock from the two most

common causes of sheep abortions in New Zealand. While this vaccination programme affords his

maiden ewes good protection from losses and disease caused by Campylobacter and Toxoplasma, when

several abortions (which were subsequently laboratory confirmed as being caused by Campylobacter)

were seen in the lambing of 2018 in the mixed-aged ewe mob, a decision was made to conduct an on-farm study. Using the EID’s, half of the previously vaccinated mixed-aged ewes were given a Campyvax4

booster prior to mating for the 2019 season, while the other half were not boosted.

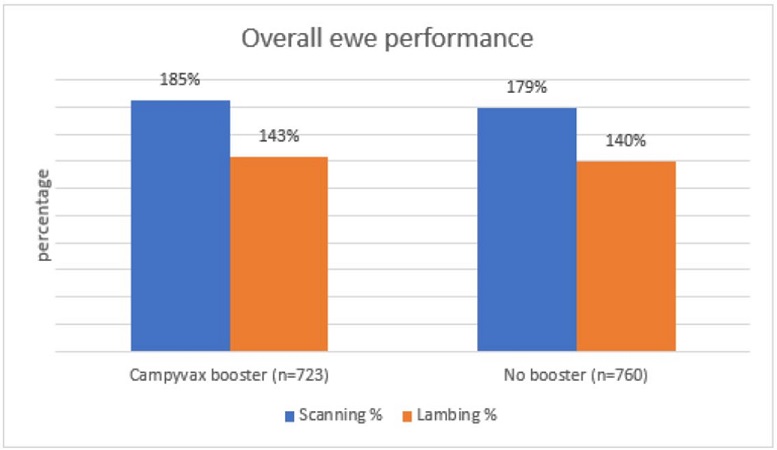

This booster, alongside some management changes over the winter months which focused on reducing

stocking rate and therefore reducing intensity and pressure, had the desired effect of reducing the

Campylobacter losses in the subsequent season (refer Figure 1), and increasing the overall scanning and

docking percentages. It also provided some great insights in respect to how farmers can get the most

from their investment in vaccines and boosters.

A particularly pertinent insight was that as a result of boosting half the previously vaccinated mixed-aged ewes in the 2019 season was that the effectiveness of the Campyvax4 was confirmed, while also

demonstrating what happens when the product is used off-label and there is an increased interval

between initial vaccination programme and boosters.

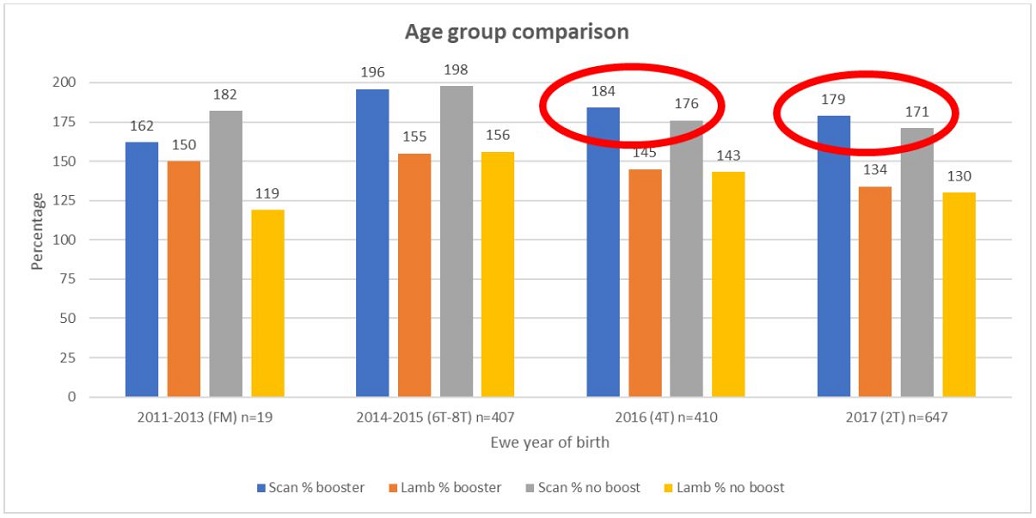

In short, what the data showed (refer Figure 2) was there was a benefit of providing ewes with a booster

in those mobs who were boosted the year after the initial vaccination course (on-label), and also perhaps those who missed a year (e.g. not vaccinated as two-tooths but boosted as four-tooths).

However, there was no benefit boosting ewes who had more than a one-year gap since the initial

vaccination course. In those older, but very high performing 2014 or 2015 born ewes, they would have

required their course of 2 shots to begin again, with a sensitiser and a booster.

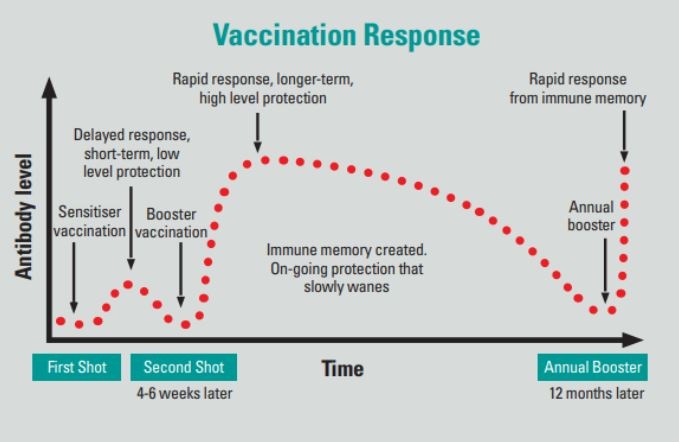

These findings align with basic vaccinology principles (refer Figure 3) which show that the booster shot

helps the body produce highly specific longer-lasting antibodies and immune cells which create an

‘immune memory’ so that if the vaccine (or natural disease) is encountered again in the future, the

animal’s immune system can respond quickly and effectively. However just like human memory,

immune memory wanes over time hence the need to ‘jog’ the memory via boosting annually which is

recommended as per label instructions.

It is important to note that some caution is required when interpreting the data given this wasn’t a fully

replicated field trial (and therefore determining whether results were statistically significant is not

possible). However due to the excellent data captured from the EID’s and genetic testing at scanning

and docking there is some valuable information obtained.

The genetic testing provided additional rigor to the data captured and subsequent findings as it allowed

lambs to be linked to their dams. In many cases ewes which were identified as “wet-dry” and appeared

to have ‘lost’ a lamb were in fact having their lambs raised by another ewe.

AVAILABLE ONLY UNDER VETERINARY AUTHORISATION. ACVM No’s: A4769 & A9535. NZ-CVX-230200004